The Medium Resolution Spectrometer (MRS) of the Mid-InfraRed Instrument (MIRI) on the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) gives insights into the chemical richness and complexity of the inner regions of planet-forming disks. Several disks that are compact in the millimetre dust emission have been found by Spitzer to be particularly bright in H2O, which is thought to be caused by the inward drift of icy pebbles. Here, we analyse the H2O-rich spectrum of the compact disk DR Tau using high-quality JWST-MIRI observations.

We infer the H2O column densities (in cm‑2) using methods presented in previous works, as well as introducing a new method to fully characterise the pure rotational spectrum. We aim to further characterise the abundances of H2O in the inner regions of this disk and its abundance relative to CO. We also search for emission of other molecular species, such as CH4, NH3, CS, H2, SO2, and larger hydrocarbons; commonly detected species, such as CO, CO2, HCN, and C2H2, have been investigated in our previous paper.

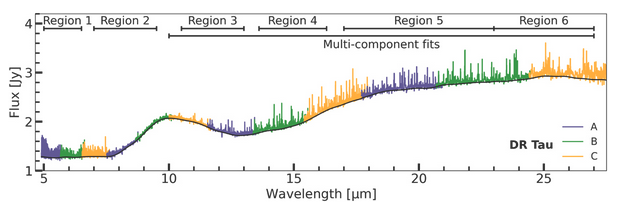

We first use 0D local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE) slab models to investigate the excitation properties observed in different wavelength regions across the entire spectrum, probing both the ro-vibrational and rotational transitions. To further analyse the pure rotational spectrum (≥10 μm), we use the spectrum of a large, structured disk (CI Tau) as a template to search for differences with our compact disk. Finally, we fit multiple components to characterise the radial (and vertical) temperature gradient(s) present in the spectrum of DR Tau.

The 0D slab models indicate a radial gradient in the disk, as the excitation temperature (emitting radius) decreases (increases) with increasing wavelength, which is confirmed by the analysis involving the large disk template. To explain the derived emitting radii, we need a larger inclination for the inner disk (i ~ 10–23°), agreeing with our previous analysis on CO. From our multi-component fit, we find that at least three temperature components (T1 ~800 K, T2 ~470 K, and T3 ~180 K) are required to reproduce the observed rotational spectrum of H2O arising from the inner Rem ~0.3–8 au. By comparing line ratios, we derived an upper limit on the column densities (in cm‑2) for the first two components of log10(N) ≤18.4 within ~1.2 au. We note that the models with a pure temperature gradient provide as robust results as the more complex models, which include spatial line shielding. No robust detection of the isotopologue H2 18O can be made and upper limits are provided for other molecular species.

Our analysis confirms the presence of a pure radial temperature gradient present in the inner disk of DR Tau, which can be described by at least three components. This gradient scales roughly as ∼R-0.5em in the emitting layers, in the inner 2 au. As the observed H2O is mainly optically thick, a lower limit on the abundance ratio of H2O/CO~0.17 is derived, suggesting a potential depletion of H2O. Similarly to previous work, we detect a cold H2O component (T ~ 180 K) originating from near the snowline, now with a multi-component analysis. Yet, we cannot conclude whether an enhancement of the H2O reservoir is observed following radial drift. A consistent analysis of a larger sample is necessary to study the importance of drift in enhancing the H2O abundances.

Scientific article:

MINDS. The DR Tau disk: II. Probing the hot and cold H2O reservoirs in the JWST-MIRI spectrum. By: M. Temmink et al. [original]